It was my fourth stay in Morocco in the fall of 2016. I was on my own, hopping around hostels and couches between the cities of Rabat and Casablanca while conducting interviews for my graduate research on the history of punk rock and heavy metal there.

There’s something about Casablanca and Rabat, two coastal cities roughly two hours apart by train, that causes them to produce very different artists. Rabat is a relatively quiet and small city in contrast to the aggressive density of Casablanca. Rabat introduced punk to Morocco in the form of ska-infused skate punk. Casablanca introduced hardcore.

I feel weird rattling off my punk credentials, but here’s a little personal background: I grew up in California’s central valley and started listening to punk rock in middle school and began participating in my local scene, playing and booking shows in the Sacramento area with my high school street punk band. When I was fifteen, I started hosting a punk show at the UC Davis radio station, KDVS.

I began studying Arabic in college, with a growing interest in the history of the Middle East, and in 2008 I went to the city of Ifrane, Morocco, for a study-abroad program. I was determined to find a punk band while I was there and succeeded in finding exactly one band.

The fact is punk rock has never been huge in Morocco. When I began my graduate research in 2016, I intended to write exclusively on the Morocco punk scene, but lacking in material to discuss, I expanded the project to include Moroccan heavy metal as well.

Metal took root in Morocco more than a decade prior to punk, with Casablanca’s Immortal Spirit, the first Moroccan metal band, forming in the mid-1990s.

A discussion of heavy metal in Morocco can’t go without mention of “the Metal Affair,” also known as “the Satanic Affair.” In 2003, a satanic panic incited by conservative parliamentarians led to the arrest members of the bands Reborn, Nekros, and Infected Brain for allegedly practicing satanism. The event incited protest and public debate regarding freedom of speech in Morocco. After a month in court, the fourteen metalheads were released.

After that, the state began to reassess its treatment of Morocco’s alternative youth, favoring cooptation over exclusion, sponsoring youth oriented events such as the Boulevard and Tremplin music festivals.

In 2004, five skaters in Rabat formed Z.W.M., the first Moroccan punk band. Their main musical influence was the bands that were popularly played in skate videos at the time, generally Epitaph and Fat Wreck Chords bands like NOFX, Rancid, Satanic Surfers, and Bad Religion. They also integrated elements of local popular music, such as Gnawa, into their brand of skate punk.

Unlike other rock bands in the country, Z.W.M. primarily sang in the Moroccan dialect Arabic. Up to that point it was widely accepted that rock music should only be sung in English or French and the idea of an Arabic-singing punk band was met of with some skepticism.

After two years of playing sporadic shows, mostly around Rabat, Z.W.M. entered and won the 2006 Boulevard competition and the band gained national recognition. By 2010 they left for France where they continue to play and record, periodically returning to Morocco to perform.

Following Z.W.M.’s departure, a second wave of punk bands spread across the country. Out of Casablanca came W.O.R.M. and Riot Stones, the first two hardcore punk bands in the country. Coming from the same neighborhood as Z.W.M., Tachamarod played a similar brand of Arabic skate punk. The Protesters played a blend of ska and street punk, and featured members of Riot Stones. From Meknes came Blast, which played politically-charged pop punk, and remains one of the only punk bands from outside of Rabat and Casablanca.

Fusion is one of the most popular genres in Morocco, generally consisting of a blend of popular traditional music, reggae, hip hop, and rock.

Betweenatna is essentially a fusion supergroup and their sound leans heavily in the direction of punk and metal. Their narrative-driven lyrics generally tell absurd stories of everyday life for youth on the streets of urban Morocco, and their whimsical performances, relatable lyrics, and scene clout has led Betweenatna to be one of the most popular bands in the country at this moment.

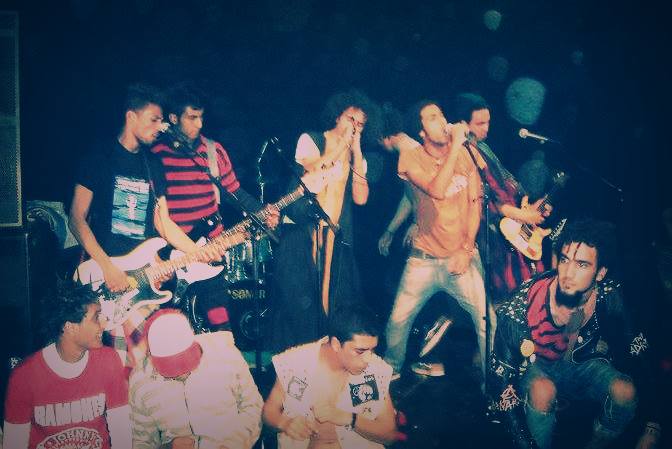

In 2016, I attended a Betweenatna show at Boultek.

The Boultek is a cultural center located in the parking lot of a mall in a Casablanca neighborhood called California. The performance space connects to a parking garage where kids can sneak off to discreetly drink and smoke hash. The large space was packed with over a hundred attendees, boys and girls mostly in their late teens and twenties. I saw kids with stick and poke Black Flag tattoos, wearing denim vests patched up with the logos of the Misfits and Ska-P, alongside individuals in Korn and Slipknot hoodies. Betweenatna played a rowdy set and drew an equally rowdy crowd. Moshing was tolerated.

During my last visit in 2018, I found little left of the punk scene I documented in my graduate research two years before. Betweenatna and Blast were the only remaining punk bands actively playing. Both Tachamarod’s frontman and lead guitarist had moved to China and France, respectively, rendering the band inactive. L’Uzine, a cultural center in the Casablanca suburb, Ain Sebaa, that had rented its venue and practice spaces to young musicians since the early 2010s had changed management and was now less friendly towards rock music, giving fusion artists preference over punk and metal musicians for use of their space. Hardzazate, a festival in Ourzazate had long billed itself as a “hardcore,” but with a dearth of local punk musicians, that year’s lineup was dominated by other types of music.

My partner and I spent the majority of our visit hanging out with Saad, the bassist of Tachamarod. He was hoping to join his bandmate in China, where they would continue to play as Tachamarod, but his visa application was denied, again.

During the last week of the visit, my partner and I traveled with Saad to Casablanca, where we hung around the new skatepark outside the old colonial cathedral in downtown. There we met a young skater who told us about the punk band she was forming, Reason of Anarchy. I have yet to hear anything more of that band, but maybe there is a future for punk rock in Morocco.